In the rapidly evolving world of digital media, the bridge between a raw camera signal and a global audience is the encoder. Whether you are managing a single executive town hall or a campus-wide lecture capture system, the choice between hardware and software encoding is the most critical decision in your technical stack.

While the “software vs. hardware” debate is often framed as a matter of preference, the reality is rooted in reliability, scalability, and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). This guide breaks down the technical nuances, the hidden costs of labor, and the operational risks associated with each to help you build a resilient video ecosystem.

Stream like a pro

High-performance hardware for video capture, streaming, and recording. With seamless CMS support for Kaltura, Panopto, Opencast, and YuJa and easily integrates with Crestron AV systems.

What is a video encoder?

A video encoder converts raw video input into a compressed digital format that can be streamed or recorded efficiently. Whether you’re sending video to a content delivery network (CDN), a learning management system, or internal infrastructure, the encoder sits at the heart of the workflow.

Encoders generally fall into two categories:

Hardware encoders: Dedicated, purpose-built devices designed specifically for encoding video. Learn more in our hardware encoder primer.

The Pearl family are all examples of hardware encoders.

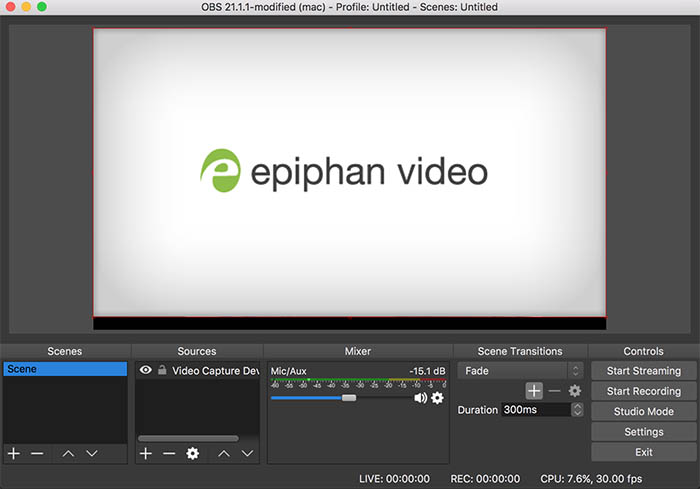

Software encoders: Applications that run on general-purpose computers or servers and rely on system resources for encoding.

A few examples of software encoders include OBS, vMix, and Wirecast.

Both can get the job done. The differences show up when reliability, scale, and operational realities enter the picture.

Hardware encoders: dedicated power and purpose-built reliability

A hardware encoder is a standalone device designed with a single mission: to encode video and audio signals into a streamable format. Unlike a general-purpose computer, these devices use dedicated chips (ASICs or FPGAs) to handle the heavy lifting of video compression.

The pros: stability and security

The primary advantage of a hardware-based streaming encoder is its “appliance” nature. Because the operating system is stripped down to only essential functions, there are fewer background processes to interrupt the video stream.

- Reliability: Hardware encoders are built for 24/7 operation. They don’t suffer from “Blue Screens of Death” or forced OS updates mid-broadcast.

- Performance: They handle real-time encoding of high-quality video (like 4K60) without the jitter often seen in multi-purpose PCs.

- Security: With no web browsers or third-party apps, the attack surface for a hardware-based broadcast encoder is significantly smaller.

The limitations: fixed capabilities

The trade-off for this stability is rigidity. A hardware device is often limited to the physical video input ports it was manufactured with (e.g., HDMI or SDI). While firmware updates add features, you cannot simply “download more RAM” if your production needs outgrow the device’s processing power.

Hardware encoder use cases

Hardware is the gold standard for high-stakes environments:

- Mission-Critical Broadcasts: Where a failure means lost revenue or reputation.

- Permanent Installations: Such as dedicated hardware encoders for lecture capture in universities, government meetings, and court recordings.

- Remote Productions: Where technical staff isn’t on-site to troubleshoot a crashed PC.

Software encoders: Flexibility vs. performance trade-offs

Software encoders (like OBS, vMix, or Wirecast) run on standard computers or servers. They take the video data from a capture card or USB source and use the computer’s CPU or GPU to encode video for streaming platforms.

Pros: The Flexibility Factor

The biggest draw of software is the UI. You can easily switch scenes, add overlays, and integrate free open source plugins to customize your streaming setup. For creators who need to change their workflow daily, software offers an unmatched playground.

Advantages of software encoders

- Low barrier to entry: Many software encoders are free or relatively inexpensive, making them attractive for experimentation or small-scale use.

- Extreme flexibility: Software encoders support a wide range of plugins, custom layouts, graphics, and integrations.

- Fast iteration: New features can be added quickly through software updates without changing hardware.

Cons: The Performance Trade-off

The Achilles’ heel of software encoding is that it shares resources. Your video and audio sync is at the mercy of the Windows Update scheduler, antivirus scans, and Chrome tabs. This “resource contention” can lead to dropped frames in your streaming video, regardless of how much processing power you have.

Limitations of software encoders

- Performance variability: Encoding quality depends heavily on system specs and what else the machine is doing. Background tasks, updates, or user error can impact stream quality.

- Higher failure risk: Crashes, OS issues, driver conflicts, and accidental configuration changes are common causes of failed streams.

- Operational complexity: Software encoders require ongoing management: patching operating systems, managing drivers, and ensuring consistent configurations across machines.

Common software encoder use cases

- Temporary or mobile productions

- Budget-constrained environments

- Highly customized live productions

- Experimental or non-critical streams

| Feature | Hardware Encoder | Software Encoder |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability | High (Dedicated OS) | Variable (OS interference) |

| Security | High (Hardened Appliance) | Low (Vulnerable to Malware/OS) |

| Staffing Requirement | Low (Plug and Play) | High (Requires IT/Tech Support) |

| Scale | Easy (Centralized Management) | Difficult (Individual Configs) |

| Physical I/O | Integrated (SDI/HDMI) | Requires External Capture Cards |

| Performance | Consistent | Varies (available processing power-dependant) |

Hardware vs software encoders: Total cost of ownership (TCO)

Upfront cost tells only part of the story. The real comparison happens when you look at total cost of ownership (TCO).

Hardware encoder TCO factors

- One-time hardware purchase

- Minimal maintenance

- Long service life (often five to seven years)

- Lower support and staffing requirements

- Predictable upgrade cycles

Software encoder TCO factors

- Licensing or subscription fees

- Cost of the host computer or server

- Ongoing OS and hardware upgrades

- Higher support and troubleshooting time

- Greater risk of downtime

The hidden line items: Labor and failure costs

When organizations compare hardware and software, they often look at the “sticker price.” A software license might cost $500, while a professional hardware appliance might cost $3,000. However, this is a narrow view that ignores the hidden line items: labor and failure costs.

Labor as an ongoing expense

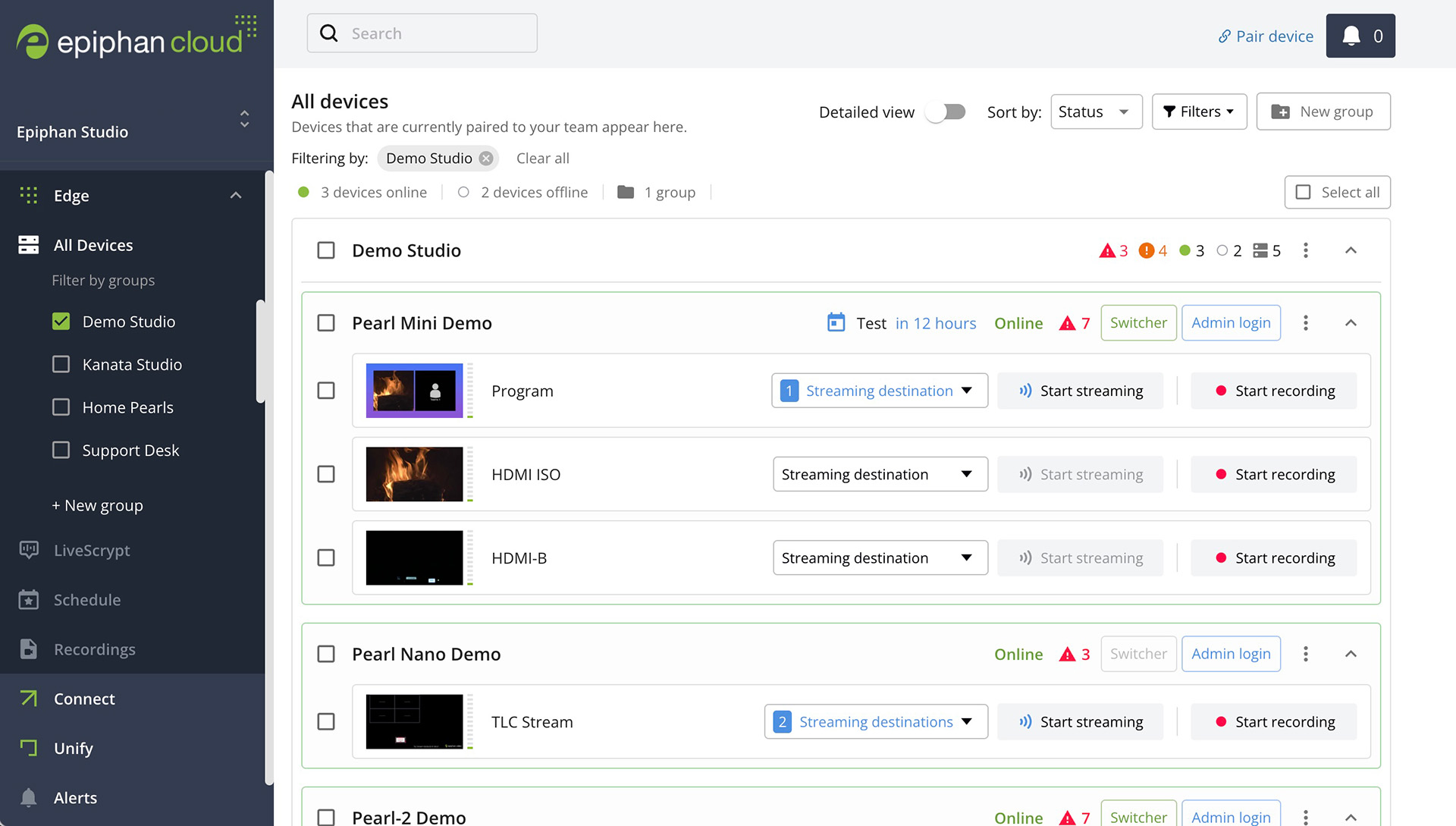

Software encoders require constant “babysitting.” A technician must ensure drivers are updated, the OS is optimized, and the hardware components (CPU/GPU) aren’t overheating. In a 50-room deployment, the man-hours required to maintain 50 separate PC configurations are astronomical compared to 50 hardware appliances that can be managed via a single cloud dashboard (e.g., Epiphan Edge).

The cost of failure

What is the cost of a failed stream?

- In Corporate: A lost hour of a CEO’s time and the attention of 5,000 employees.

- In Education: A lost lecture that cannot be replicated for remote students.

- In Event Production: Refunded tickets and a damaged brand.

If a software-based streaming setup fails 2% more often than a hardware setup, that 2% downtime quickly outpaces the initial “savings” of the software license.

TCO comparison: A 3-5 year outlook

TCO isn’t just about dollars; it’s about operational risk.

Scenario A: The single room (small scale)

For a single hobbyist streamer, a software encoder on an existing PC is the most cost-effective. The “labor cost” is the user’s own time, which is often valued at zero.

Scenario B: The enterprise deployment (50 rooms)

Imagine equipping 50 hybrid meeting rooms.

- Software Approach: 50 PCs, 50 Windows licenses, 50 capture cards, 50 software seats. You need a dedicated IT person just to manage the updates and troubleshooting. Over 3 years, the labor and “crash-related” lost productivity can exceed $150,000.

- Hardware Approach: 50 all-in-one video production systems that are “set and forget.” Maintenance is centralized. The risk of a “forced update” killing a meeting is near zero. The TCO is higher upfront but significantly lower in operational man-hours and risk-adjusted loss.

Over three to five years, hardware encoders often cost less overall in environments where reliability and scale matter.

Performance benchmarks and real-world testing

In real-world testing, the difference in video compression efficiency is often negligible between the two, as both utilize standard codecs like H.264 or HEVC (H.265). However, the encode and decode latency is where hardware shines.

Hardware encoders often feature “sub-second” latency, which is vital for interactive video content or remote surgery applications. Software encoders, burdened by the operating system’s “buffer layers,” typically introduce 1–3 seconds of additional latency.

Furthermore, hardware is better at creating smaller files without sacrificing high-quality video. Because the chips are optimized for specific math operations required by H.264, they can produce a more efficient bit-to-quality ratio than a general-purpose CPU.

Decision matrix: When to choose which?

Choose a hardware encoder if:

- Failure is not an option: (e.g., Live surgery, graduation ceremonies).

- You need to scale: You are managing more than 3 locations.

- You want to minimize labor: You don’t want to hire a full-time tech to “nurse” the computer.

- Security is a priority: You are operating on a government or corporate network.

Choose a software encoder if:

- Budget is the only constraint: You already own a powerful PC.

- Visual complexity is high: You need 20+ layers of graphics and moving elements.

- Experimental workflows: You are testing new, free open source tools that aren’t yet standardized in hardware.

Hardware vs. Software Encoder Decision Table

| Choose a Hardware Encoder if… | Choose a Software Encoder if… |

|---|---|

| ✅ Reliability is critical | ✅ Flexibility is essential |

| ✅ Security is a top concern | ✅ Budget is tight |

| ✅ Scalability is a must | ✅ Small-scale or temporary setup |

| ✅ Dedicated operation is needed | ✅ In-house expertise available |

| ✅ Minimal setup and maintenance | ✅ Frequent updates are required |

Integration considerations and workflow impact

A video encoder comparison isn’t complete without looking at the workflow. Encoders don’t exist in isolation. They sit inside broader AV and IT workflows.

Hardware encoders integrate cleanly into:

- Networked AV environments

- Centralized device management platforms

- Automated scheduling systems

- Secure enterprise and government networks

Software encoders integrate best with:

- Creative production tools

- Graphics and switching software

- Operator-driven live productions

The right choice depends on who operates the system and how often it needs to run without intervention.

Hardware encoders, like the Epiphan Pearl family, often integrate directly with platforms like Panopto, Kaltura, or Opencast. This means the video and audio are automatically pushed to the cloud, titled, and sorted without human intervention.

Software encoders often require “manual” file management. After you encode video, someone has to ensure the file is named correctly and uploaded to the right folder. This “human-in-the-loop” requirement is another hidden labor cost that increases the risk of lost video data.

For organizations standardizing on dedicated devices, purpose-built appliances like a dedicated hardware video encoder for streaming and recording simplify deployment and long-term support. Centralized management platforms, such as cloud-based encoder management and monitoring tools, further reduce operational overhead at scale.

Future trends: The hybrid solution

The future of video encoding is moving toward a hybrid model. This involves using a versatile hardware video encoder for the heavy lifting of the video stream while using cloud-based software for switching and graphics.

This “Best of Both Worlds” approach allows you to keep the rock-solid reliability of hardware at the source (the “edge”) while maintaining the creative flexibility of software in the cloud. As streaming video moves toward 8K and AV1 codecs, the need for dedicated hardware will only grow, as these formats require even more processing power than standard PCs can reliably provide while multitasking.

Final thoughts

Choosing between a hardware and software encoder is a choice between flexibility and predictability. For hobbyists and individual creators, software is a powerful, low-cost entry point. But for organizations, the “cheap” software option often becomes the most expensive line item on the balance sheet due to labor, maintenance, and the high cost of technical failure.

When your brand, your message, or your revenue depends on a consistent video stream, the investment in a hardware-based streaming setup is an investment in peace of mind.